Capacity-building for systemic change

Mille Bojer

June, 2011

Category

Topics

Capacity building is an integral part of systemic intervention. Learn the why, what, and how of capacity building for systemic change.

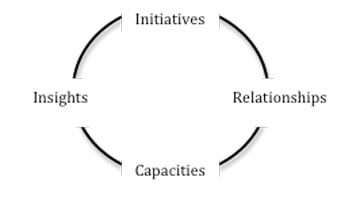

Every change effort we engage in at Reos Partners has its own distinct purpose and objectives specific to the system we are trying to influence—be that child protection in Australia, business sustainability in Brazil, or food security in South Africa. At the same time, in our work with diverse Change Labs, we have found that these projects commonly generate four key intermediate results that together help to achieve systemic change. These outcomes include:

- Deep insights and understanding into the workings and potential of the system;

- Innovative, systemic prototype initiatives that serve as “living examples” of a new reality;

- Strong, trusting relationships among key players in the system; and

- Strengthened individual and collective capacities.

Systemic change does not result from any one of these results alone but from the interaction and combination of all four. Projects may end, but relationships, understanding, and fresh capacities can sustain a system’s continued ability to generate new initiatives, partnerships, structures, and ongoing solutions in the face of complex challenges.

Of these four results, the concept of “capacity” is possibly the most elusive, even though it is also the one that tends to be most successfully achieved in the Change Labs. On their evaluations of the Change Lab experience, participants often emphasise what they learned and how the process made them more effective in their work.

People external to the process, such as funders, may wonder why this focus on capacity is so important and why the Change Lab is so “personal.” We have found that many efforts to create social change assume that people already have the capacity to work together, talk and listen effectively, and move the change process forward, or that, if people need training in these areas, they receive it in a classroom setting outside the workspace.

I see this assumption as a missed opportunity. A successful systemic intervention often involves capacity building as an integral part of the process. This article is intended to stimulate conversation on the why, what, and how of capacity building for systemic change.

What capacities are needed?

At Reos, one of our primary goals is to strengthen people’s capacity to co-create and sustain change in the face of complex social problems. But what does that mean and what does it entail?

The Change Lab generally utilizes a creative method known as the U-Process, articulated by Otto Scharmer in his book, Theory U. The U-Process outlines a sequence of activities (seeing, sensing, presencing, and prototyping) as well as the capacities needed to engage effectively in those activities, including suspending, redirecting, letting go, letting come, enacting, and embodying. The model makes both the external activities and the internal capacities explicit. This approach is not common; most change methodologies spell out what to do and how to do it without mention of what capacities we need to be successful in those activities.

At Reos, we’re continually exploring the capacities that are needed in the complex environments in which we operate. Just as capacity building is an ongoing and lifelong process for an individual, identifying the needed capacities is an ongoing conversation for groups involved with social change. If we gathered all Reos partners and collaborators, we could easily generate a list of 50 capacities we want to develop in ourselves and others. But rather than creating a long, intimidating menu that applies across the board, we have found that every group and each person needs to decide where to focus to best advance their own objectives.

When my Reos colleague Busi Dlamini and I worked on a capacity development programme for HIV/AIDS service providers in Alexandra township in South Africa a few years ago, we asked the group, What capacities do you want to develop? They created a fascinating list. Out of the ensuing conversation, group members articulated that one of the capacities they wanted to develop was the capacity to build their own capacity. They recognized that they wouldn’t be able to achieve this goal through a training course but rather would need to develop an emergent and experiential group process and reflect on their practice.

One simple framework that can be helpful in identifying the capacities we need is to explore the potential and balance of “head, heart, and hands” or “thinking, feeling, and doing”. What are the capacities of the “head” that we need to co-create social change? Some possibilities include imagination, openness, creativity, and systemic thinking. Which are the capacities of the “heart”? They include purpose, empathy, presence, and courage. And of the “hands”? Initiative, persistence, entrepreneurship, and collaboration are valuable in this area. Different individuals and groups will focus on different capacities at different times.

Multiple levels

Capacity is not only an individual concept, but also a collective idea. Capacity exists and can be developed at the level of a team, organisation, network, sector, and society. Reos works in parallel at the individual and the collective level and we find that this multi-level work is crucial to creating systemic change.

In the U-Process, the capacity to “sense” is different from the capacity to “co-sense”. In a recent Change Lab course in Brasilia, the group divided into three sub-groups to go on learning journeys to explore political participation in Brazil. In debriefing the experience, we noticed that just as we all have various sensory organs that we use on such a journey, so each person can act as a sensory organ for the sub-group, and each sub-group as a sensory organ for the whole.

In every Change Lab course in which I have been involved, one of the key lessons has been the deeper understanding that comes from the shared experience in co-sensing, co-presencing, and co-creating. As we learn from systems thinking, our collective capacity can be greater than the sum of our individual capacities. We can’t achieve systemic change only by developing the parts. The collective capacity of a group, organisation, or network depends greatly on the relationships among the people involved, the quality of their interactions, and the clarity of the collective understanding of purpose, principles, and values.

To build this collective capacity in a particular social system, we need to involve people from various stakeholder groups in the process. In South Africa, Reos and others convened a group of leaders working with vulnerable children affected by HIV/AIDS, malnutrition, and broken families. The initiative is called the Leadership and Innovation Network for Children (LINC / www.linc.org.za). It has sustained its relevance over five years because it places so much emphasis and effort on getting the right people across the system into the room. The original convening process for LINC took a year and a half; the group was formed through a careful and attentive interviewing, inviting, encouraging, and networking process.

At the first workshop in 2007, participants felt a strong sense of having the “system in the room”. In addition to the projects that emerged, people noticed the positive effect of strengthened relationships, collective insights, and the enhanced capacity of the key stakeholders on the system’s overall capacity. The process is ongoing: Every year, a new recruitment drive brings in another cohort of leadership into LINC, and at the same time, some people chose to leave because they are no longer the right people.

The inner and the outer

I recently contributed a chapter to a new book entitled Capacity Development in Practice. In this book, the editors make the point that capacity can only express itself in action. It’s about how effectively we function and how we achieve results that make a difference in people’s lives. Using the examples from to the introduction to this article, we are talking about the real ability to protect children, establish food security, create and manage an environmentally, socially, and financially sustainable business, and so on.

While capacity can only be expressed and assessed in action, it is also best developed through action. We achieve our impact on the world largely through our capacity, and we build our capacity through the practice of our real work in the world. Kurt Lewin emphasised that we only really understand a system when we try to change it. We also only know our capacity when we test it in action.

This is part of the reason why in our three-day courses on the Change Lab (as mentioned in the toolkit article of this newsletter by LeAnne Grillo), we have chosen a real-life theme to work on in each course. Here in Brazil, these have included political participation, sustainable consumption practices, education, waste management, sustainable mobility, climate change, health care, and social division. The theme always focuses on a system that involves everyone, so it is a case study but it is also real. The more participants manage to engage fully with the case study, the more they will gain from the course.

In our courses, we also emphasise experiential learning and prototyping. Doing so enables us to reinforce this cycle of building capacity through action and creating an impact through building capacity.

Reflection on practice

Learning through action works best when we consciously incorporate moments for reflection on our practice, before and after an activity. Some approaches that work well for strengthening this capacity include doing warm-up exercises, naming/making conscious the capacities we are working on at each step, suggesting what kind of stance participants could take during the upcoming activity, and journaling to become aware of one’s feelings and assumptions upon embarking on the activity. After an activity, it helps to again give time for journaling, debriefing in the group, and reflecting not only on the content but also on the experience and on what participants observed about themselves.

In Reos Brazil, we recently asked all previous Change Lab course participants to evaluate the impact the courses had had on them in terms of initiatives, relationships, insights, and capacities. A number of people highlighted the value of the small awareness practices such as taking moments of silence to retreat and reflect, even if briefly, before acting; and doing an exercise before a meeting or an interview to become aware of one’s preconceptions in order to suspend them. I think this is what it means to build one’s capacity to build one’s capacity.

Coaching

Because building capacity is inherently action-oriented and situational, we have found coaching to be a useful tool. This includes coaching individuals and project teams during a project around questions such as, What capacities are you working on? What are you trying to achieve and how might you be more effective?

One of our recent initiatives in Reos São Paulo was the GRES project (Corporate Sustainability Reference Group), created in partnership with the Instituto Ethos (www.ethos.org.br). This project involved 13 Brazilian and international companies in an effort to improve their sustainability practices. Over the course of the Change Lab, individual participants received up to three coaching sessions from the Reos facilitators, and when they started developing initiatives, some coaching was also provided for the initiative teams. Coaching calls happened between workshops, and it was striking to see from one workshop to the next the impact that the conversations had on some participants. In the sessions, they had a chance to talk through what was going on in the process, what capacities they particularly were working on, and what challenges they were facing. As a result, they shifted their behaviour and increased their effectiveness. In this way, the coaching sessions offer another type of iterative cycle between individual and collective reflection.

We are further developing our coaching practice and approach in Reos at multiple levels, including coaching for Reos partners to improve our own capacity to do our work; coaching as an integral part of our Change Lab projects; and coaching as a service for change agents and leaders.

Conclusion

Former CEO of Hanover Insurance Company Bill O’Brien said, “the success of an intervention depends on the interior condition of the intervenor.” We often highlight and draw inspiration from these words. I believe it is not only about the interior condition of the intervenor but also the interior condition of the stakeholders and of the collective. All of this is capacity building. If we want to change systems, we have to also change ourselves, not before, not after, but as an integral part of the social change process.

Of course, the interior condition isn’t the sole success factor. Systems thinking is about understanding the connections and patterns between the whole and the parts, embracing the interplay between the inner and the outer, and knowing when to zoom in and when to zoom out. Developing this capacity is one of the constant challenges of our work and part of what makes it so rewarding.

References

Capacity Development in Practice, edited by Jan Ubels, Na-aku Acquaye Badoo, and Alan Fowler (Earthscan, 2010).

Theory U: Leading from the Future as It Emerges, by C. Otto Scharmer (Berrett-Koehler, 2009)

To learn more, read Mille Bojer's contribution to Capacity Development in Practice, edited by Jan Ubels.