Building Together for Our Children: Lessons from a Journey of Collaboration

Maaiane Knuth

December, 2010

Category

Topics

In 2007, I had the privilege of becoming part of a collaborative effort to demonstrate to people throughout South Africa that it is possible to take care of all of our children. In response to the overwhelming number of orphans and vulnerable children in the country, the Hollard Foundation initiated a process, in partnership with the Department of Social Development, to work to shift the system of childcare in the geographical location of the Midvaal municipality (some 40km south of Johannesburg). One of the goals was for the lessons learned from this initiative to serve the country as a whole. To help them in this undertaking they brought in Convene Venture Philanthropy and Reos Partners.

We agreed to undertake our efforts to serve the children of Midvaal through a “Change Lab” process to build leadership, collaboration, and innovative action. In brief, a Change Lab is a multi-stakeholder effort to address a specific complex challenge in a given social system. Forty-five leaders from the municipality, several government departments, non-governmental organisations, local community organisations, and businesses came together in the Change Lab. They named the collective effort “Kago Ya Bana,” which in Sotho means “building together for our children.”

Three years later, a strong collaborative platform has been established among key stakeholders and service providers; leadership has been built among more than 80 community members; childcare forums have been set up in seven communities, mobilising and organising efforts to identify and connect children in need with formal service providers; and an integrated referral and tracking system has been established to monitor the most vulnerable children. In addition, parents in the communities have set up parenting forums and classes, in which more than 1,000 people participate each year.

A recent review shows that parents’ exposure to these programs has shifted their sense of their role and has helped mobilise them in addressing their personal challenges (for example, by participating in sewing groups to generate additional income). Finally, a youth network has been established linking and enabling partnership among youth organisations in Midvaal. It has brought several new youth service providers into Midvaal and led to the establishment of a Youth Development Centre in the municipality.

The participants in the Change Lab process, which focused on the childcare system, hadn’t anticipated these last two developments, and yet these initiatives emerged as two trends became clear: the lack of capacity among parents to shoulder their role as primary caregiver, and the lack of opportunities in Midvaal for children as they leave early childhood and move into early adolescence.

Connecting with Each Other’s Contexts and Realities

These results are all important, and yet what is emerging for us in Midvaal is the idea that perhaps our ultimate innovations were not the wonderful projects or organisations created through the Change Lab, but rather the establishment of a new way for the players in the childcare system in Midvaal to relate to each other. The resulting partnership between parties who weren’t engaging with each other before has enabled ongoing individual and collective action on behalf of the children. The lessons we learned through this journey therefore primarily involve understanding each other and finding ways to be in a generative relationship.We can trace the significance of these lessons back to the reality before KYB, where in Midvaal, like in many other municipalities, the support systems for orphans and vulnerable children were fragmented and compartmentalized within different government departments, NGOs, donor groups, community organisations, and so on. Each entity was busy with its own agenda and faced its own challenges. As a result, people were trapped in silos that they didn’t know how to escape, cut off from the richness of diversity of thought and experience found in outside organisations. The Change Lab placed a great emphasis on the microcosm coming together so that participants could connect with each other’s contexts and realities, and see a broader picture of children’s services in Midvaal.As people connected to each other in novel ways, they felt a strong sense of excitement and possibility. This renewed energy led to several innovations that produced tangible results. Our challenge—which is at the heart of this article—was in sustainably embedding these more collaborative, learning-focused, and emergent ways of working with people who were often overworked, overwhelmed, and constrained by bureaucratic impediments. During the early stages of the project, one of the participants from the Department of Social Development had expressed his enthusiasm for the different way of working that Kago Ya Bana introduced. He later lamented how the bureaucracy style was creeping back into how things were being done.

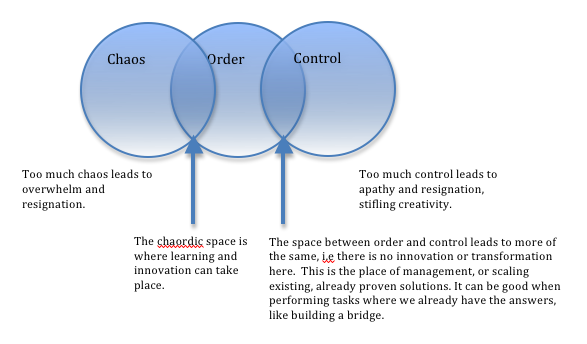

A Model of Chaos and Order

To share my insights around the challenge outlined above, let me begin by introducing a model of chaos and order, which is a part of my emerging clarity. In the past several decades, new sciences have challenged the idea of a mechanistic universe, which was introduced by Newton in the seventeenth century. A clockwork universe has no real place for chaos, but the new sciences include a notion of chaos as an unavoidable and necessary part of life. My experience is that most of us consider chaos as something to be feared and avoided at all costs.The living systems view invites us to remember that change, or transformation, happens on the edge of chaos. Chaos provides the needed energy for transformation, out of which a system can self-organise on a higher level than before, i.e. being able to hold a greater degree of complexity. Yet, when chaos strikes—when life happens—our knee-jerk response is to seek to manage things, perhaps in the mistaken belief that in command and control we can find safety. However, I would like to suggest that, when we shy away from the possibilities that chaos can give rise to, we are also shying away from the potential of learning and innovation. If we are to reap the benefits that life offers, we need to stay and make our way through the chaos, learning to walk the edge between disorder and order. At this edge, just enough order exists for there to be coherence, but not so much as to slow learning and adaptation. Whenever I have erred on the side of order, or even control, I have paid the price by limiting the learning and creativity of those I work with in the process.

This place between chaos and order is what Dee Hock has termed “chaordic” in his book Birth of the Chaordic Age. He believes we need more chaordic organising and organisation. At its essence, this concept is about learning to developing structures and practices that allow for freedom and self-organising around a clear and consistent core. A complementary view, which gives hints about what might be required to achieve this state, comes to us from biology. In his book The Power of Spirit: How Organizations Transform, Harrison Owen defines the following essential pre-conditions for self-organising, drawn from the work of theoretical biologist Stuart Kauffman:

- A nutrient-rich, relatively protected environment

- A high level of diversity and potential complexity in terms of the elements present

- A drive for improvement

- Sparse pre-existing connections between the various elements

- All (the whole mess) at the edge of chaosThis framework has been incredibly helpful to me. It means that for anything to come out of the potentiality that chaos offers, at a minimum, we need a “relatively protected environment”—a safe space. Not too safe, but safe enough. We also need a high level of diversity with sparse pre-existing connections, which is inherent in the Change Lab: In working with complex social problems, we bring together a microcosm of the whole that may never have been connected before. Finally, we need a drive for improvement—a shared purpose—something that, in my experience, is a vital organising and mobilising force.

A “Safe Enough” Space

These lessons from nature have helped me recognise that one of our key lessons in Midvaal was around the challenge of creating a safe enough space in which to skirt the edges of chaos and invite in the new. In the KYB project, we sought to help bring forth social innovations through the Change Lab. As new ideas emerged that we needed to quickly test on the ground, old modes of control got in the way: controls around spending money, around reporting requirements, and sometimes even around meeting protocols. The process was supremely frustrating—and entirely understandable.South Africa is a young, highly diverse democracy on a steep learning curve. The challenge of the orphaned and vulnerable children—one of many challenges—is without precedent. In this context, chaos abounds. Add to this uncertainty was the fact that many of our lab team members came from backgrounds of poverty and marginalisation, and thus were unfamiliar with navigating the demands of “the system.” The natural response in dealing with this kind of reality tends toward one of control, in particular by those holding the purse strings.It was therefore not surprising that people could not hear or understand me when I challenged them to loosen their need to control the process and its outcomes, and to trust letting people experiment and create what they most cared about, within the bounds of purpose and agreed-on principles. I wanted us to operate on the edge between chaos and order, but began to see that perhaps we needed to make our way gradually, even gently, from where we found ourselves, in a paradigm of control, to a more natural order before embracing this edge.In some ways, this disconnect felt like a moment of failure for me. I had to let go of some of my deeply held beliefs around participation in order to respond to the very real need being expressed by the partners for a stronger sense of regularity or control of the process. And yet the gift of KYB has been a deeper lesson: That fundamental to the journey from control to order is the quality of our relationships.

The Quality of Relationships

In Reos, we have seen that Change Labs produce four key results: new ideas, new intentions, new actions, and new relationships. Although we set out looking for all of these, in Midvaal, we realised that new relationships are imperative to the sustainability of all the other outcomes. We learned this lesson through on-the-ground experience. Several of the initiatives from the KYB project showed potential for having profound systemic impact, and yet two years into the process, as they were becoming fully operational, it became clear that at the level of the whole, there was still a critical gap.The formal players and partners showed up regularly to assist and support the institutionalisation of the innovations, but because this work was often over and above their formal work roles, many began to fall away. We recognised that it was vital to focus on the overriding partnerships for children in Midvaal. The innovations had built new working relationships and organisations, and now there was a need to continue attending to the whole—an ongoing learning process in which partners and community members could engage week to week, month to month, to respond to needs and challenges as they emerged. This recognition marked the beginning of a period in which the microcosm came together not simply to focus on the innovations as new ideas and practices but to focus on their relationship and as partners enable each other to do their respective roles better. Out of this insight, important seeds have been planted. Some have been quick wins; for example, through this platform, the municipality realised that children in the Mamello community were playing in the dump because they couldn’t get to school. A school bus now operates there. But perhaps more important is the initiation of new collective engagements that is occurring. From this initiative, the group recognized an urgent need in the area of early childhood development, which has led to a district-wide collaboration in the Mamello area with all the main stakeholders. The same participatory engagement methods used in KYB as a whole are being brought into this new collaboration, and the lead governmental departments are experimenting with them as a model for the province, having seen the high impact of helping a system to see and more deeply connect to itself.Thus an important partnership platform has now been established in which key stakeholders come together regularly to learn together and to identify solutions to challenges beyond the silos of departments, roles, and organisations. While we still haven’t arrived at a model for the country as a whole that clearly demonstrates that it is possible to care for allof our children, it seems to me that through this continuing journey, the people of Midvaal have shown that we can come together across great diversity and build something out of new connections and deeper relationships.

The End of the Journey

And so, at the end of this journey, at its deepest level, this work is about relationships. I have come to think of it as building a community of those people who share a common purpose; a community that allows them to be in an enabling and generative space with each other, and thus more able to navigate the edge of chaos. I think that the next step is for us to more intentionally work as a community in an emergent space.In Midvaal, once the collaboration became about genuinely supporting each other and our respective organizations to better be able to serve the children—in a diversity of ways—it was clear that everyone could benefit from being in relationship. And so at the most basic level, perhaps we are learning the power of creating a platform, our “safe enough space,” to think together and choose actions, guided by a clear, compelling, and shared purpose under which our diversity has free rein to express itself.

Acknowledgements

Harrison Owen, The Power of Spirit: How Organizations Transform. Resources on creating chaordic organisations can be found on the Chaordic Commons, www.chaordic.org. Resources on navigating the chaordic terrain more generally can be found on The Art of Hosting website, www.artofhosting.org.

The Reos team in Midvaal includes Vanessa Sayers, Roger Dickinson, Dineo Ndlanzi, and Busi Dlamini.